CLICK HERE FOR INFORMATION ABOUT DE-ESCALATION SKILLS AND TACTICS

Consensus decision making

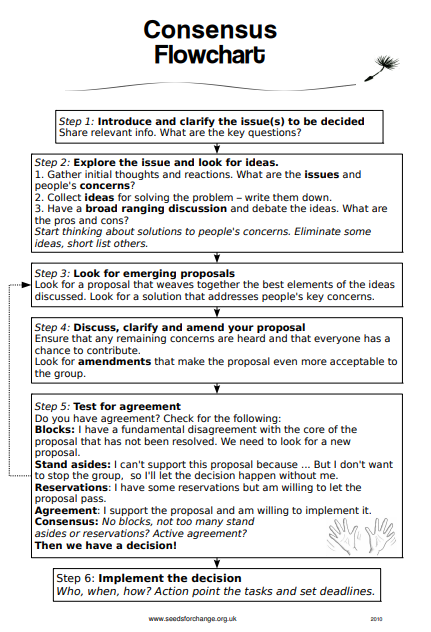

The Consensus Flowchart image below shows a simple explanation of the consensus process, and it is followed by a longer, more detailed, text explanation + example of what a consensus process (discussion) may be like for an AG.

Conditions for using consensus

It is much easier to use consensus in an ongoing way if the right conditions are in place: below are some key factors. If your group is struggling, this checklist should help identify underlying issues you need to address in order to have a better experience of consensus. Alternatively, if your group is far away from meeting these conditions you may decide that consensus isn't right for you at this moment.

Common Goal: Everyone present at the meeting needs to share a common goal and be willing to work together towards it. This could be the desire to take action at a specific event, or a shared vision of a better world. Don't just assume everyone is pulling in the same direction – spend time together defining your aims and how you expect to achieve them. If differences arise in later meetings, revisiting the common goal can help to focus and unite the group.

Commitment to reaching consensus: Consensus can require a lot of commitment and patience to make it work. Everyone must be willing to really give it a go. This means being deeply honest with yourself (and the rest of the group) about what you really need to happen, and what is just a preference. Consensus requires flexibility and being open to alternative solutions. It would be easy to call for a vote the first time you struggle to reach agreement, but in the consensus model, differences help to build a stronger and more creative final decision. Difficulties can arise if individuals secretly want to use majority voting, just waiting for the chance to say "I told you it wouldn't work."

Trust and openness: Consensus relies on everyone giving honest information about what they want and need - and being clear about the distinction between the two! This is hard if we don't trust everyone's good intentions. When we think that other people are manipulating the process or exaggerating what they need in order to get their own way, we are much more likely to do the same. Another common behaviour when we don't trust people is to close down and not express our own needs and views at all. Either way, the group does not end up with the accurate understanding of everyone's needs that enables us to look for win-win solutions. Trust can also break down if decisions are made and not implemented. As mentioned earlier in this guide, accountability is very important; both individually and collectively.

Sufficient time: for making decisions and for learning to work by consensus. Taking time to make a good decision now can save wasting time revisiting a bad one later.

Clear process: It's essential for everyone to have a shared understanding of the process that the meeting is using. There are lots of variations of the consensus process, so even if people are experienced in using consensus they may use it differently to you. There may also be group agreements or hand signals in use that need to be explained. Hand signals are sometimes used to express consensus choice on a specific decision when speaking may not be suitable due to security protocol concerns.

Active participation: If we want a decision we can all agree on, then we all need to play an active role in the decision making. This means listening to what everyone has to say and pro-actively looking for solutions that include everyone, as well as voicing our own thoughts and feelings.

Good facilitation: When your group is larger than just a handful of people or you are trying to make difficult decisions, appoint facilitators to help your meeting run more smoothly. Good facilitation helps the group to work harmoniously, creatively and democratically. It also ensures that the tasks of the meeting get done, that decisions are made and implemented. If, in a small group, you don't give one person the role of facilitator, then everyone can be responsible for facilitation. If you do appoint facilitators, they need active support from everyone present.

Knowing who should be included: A consensus decision should involve everyone who will be fundamentally affected by the outcome - rather than the people who happen to attend the meeting where it is discussed! In groups where there are different people at each meeting it can be hard to know which of the new people will end up getting fully involved. And to complicate things further, many groups have members who are involved in carrying out decisions, but can't (or don't want to) come to meetings. Getting clarity about what kind of involvement people want, and being flexible about different ways to input into a decision can help individuals have their fair share of influence. [This may not be a suitable option for some AG’s]

Options for agreement and disagreement:

There are many different reasons why someone might not agree with a proposal. For example, you might have fundamental issues with it and want to stop it from going ahead, or you might not have time to implement the decision or the idea just doesn't excite you.

Consensus decision-making recognises this – it's not trying to achieve unanimity but looks for a solution that everyone involved is OK with. Not all types of disagreement stop a group from reaching consensus. Think about it as a gradient or spectrum from completely agreeing to completely objecting to a proposal.

The words used to describe the different types of agreement and disagreement vary from group to group. It's important to be clear in your group what options you are using and what they mean. Here are some common options:

Agreement

"I support the proposal and am willing to implement it."

Reservations

"I still have some problems with the proposal, but I'll go along with it."

You are willing to let the proposal pass but want to register your concerns. You may even put energy into implementing the idea once your dissent has been acknowledged. If there are significant reservations the group may amend or reword the proposal.

Standing aside

"I can't support this proposal because... but I don't want to stop the group, so I'll let the decision happen without me and I won't be part of implementing it."

You might stand aside because you disagree with the proposal: "I'm unhappy enough with this decision not to put any effort into making it a reality."

Or you might stand aside for pragmatic reasons, e.g. you like the decision but are unable to support it because of time restraints or personal energy levels. "I'm OK with the decision, but I'm not going to be around next week to make it happen."

The group may be happy to accept the stand aside and go ahead. Or the group might decide to work on a new proposal, especially where there are several stand asides.

Blocking

"I have a fundamental disagreement with the core of the proposal that has not been resolved. We need to look for a new proposal."

A block stops a proposal from being agreed. It expresses a fundamental objection. It means that you cannot live with the proposal. This isn't an "I don't really like it" or "I liked the other idea better." It means "I fundamentally object to this proposal!" Some groups say that a block should only be used if your objection is so strong that you'd leave it the proposal went ahead. The group can either look for amendments to overcome the objection or return to the discussion stage to look for a new proposal.

Variations on the block

The block is a defining part of the consensus process; it means no decision can be taken without the consent of everyone in the group. Ideally it should be a safety net that never needs to be used - the fact that the option is there means the group is required to take everyone's needs into account when forming a proposal. Because it is such a powerful tool, some groups have developed additional 'rules' about how and when it is to be used.

Limiting the grounds on which someone can block

Some groups introduce a rule that the block is only to be used if a proposal goes against the core aims and principles of the group, or if a proposal may harm the organisation rather than because it goes against an individual's interests or ethics. For example, a member of a peace group could legitimately block others from taking funding from a weapon's manufacturer. On the other hand, if they had a strong objection to receiving money from the tobacco industry this would be seen as a purely individual concern, and they wouldn't be allowed to stand in the group's way.

Some people object that placing this kind of limitation on the reasons for blocking goes against the principle that every decision should have the consent of everyone involved. Also, in practice, it can be hard to find agreement on whether a proposal is or isn't against the aims of the group. On the other hand, particularly in groups where 'natural' commitment to the collective is low (for example because the membership is constantly changing, or the group is a very small part of people's lives) then placing a limit on the reasons for the block can prevent abuse of power.

Requiring people who block to help find solutions

A variety of groups require anyone blocking to engage in a specific process to find a resolution, such as attending extra workshops or additional meetings. This provides a clear process for finding a way forward. The time commitment required for this also 'raises the bar', with the assumption that people will only block if they feel really strongly and are committed to finding a solution. Be aware though that 'raising the bar' like this will make it disproportionately hard for some people to block, for example if their time and energy are limited by health problems or caring responsibilities.

The consensus process:

Example of how the consensus process can work

Stage 1: What's the issue

"The bit of wasteland that we've used as a park for the last ten years is going to be sold by the council."

[More information is shared.]

"So I guess the decision we need to make right now is whether we want to do anything about it, and if so, what."

Stage 2: Open up the discussion

"Let's go round and see what everyone thinks."

"I guess it's time to find somewhere else for the kids to play."

"I can't believe it. I've been so much happier since I've lived next to a park."

"But I don't think we should give up that easily! There's lots of things we could do..."

Stage 3: Explore ideas in a broad discussion

"Let's collect some different ideas of what we could do, and then decide if we want to go ahead with any of them."

"Let's raise money and try to buy the park."

"What about squatting?"

"Mmm... not sure squatting is for me! I'd be happy to look at how to raise the money, though."

[more ideas are talked about]

Stage 4: Form a proposal

"So what are we going to do? Some of you feel that we should build treehouses in the park to stop the developers, but we think we should try and raise money to buy the land."

"But nobody's said that they're actually against squatting the park – just not everyone wants to do that. And squatting might slow the council down so we have time to raise the money. Let's do both!"

[Lots of nodding; some people speak in agreement]

"That idea had lots of support, let's go round to see how everyone feels about it as a proposal."

Stage 5: Amend the proposal

"I like the idea of both squatting and trying to raise the cash to save the park, but people have been talking about separate groups doing those. I feel that we really need to stay as one group – I think if we split they might try to play one group off against the other."

[Everyone else has their say]

"OK, so there's a suggestion that we amend the proposal to make it clear that we stay as one group, even though we're both squatting and raising funds at the same time."

Stage 6: Test for Agreement

"Right, we have a proposal that we squat the park, and at the same time we start doing grant applications to raise the money to buy the land to save the park for everyone. We're want to be clear that we are one group doing both of these things. Does anyone disagree with this proposal? Remember, the block stops the rest of the group from going ahead, so use it if you really couldn't stay in the group if we followed this plan. Stand aside if you don't want to take part in the plans. If you think we should consider any reservations you have then please let us know, even if you're still going to go along with it."

"Yes, I've got reservations about the fundraising idea - I don't think it's realistic and I'm worried it's a waste of time. I won't stop you though, and I'm happy to help a bit."

"Does anyone else disagree? No? OK, I think we've got consensus. Let's just check – hands up if you agree with the proposal... Great, we have consensus, with one reservation."

Stage 7: Work out how to implement the decision

"OK, so we've taken on two really big jobs! Shall we split into two groups for now, and start idea-storming what needs doing for each, then we can bring it all back together at the end of the meeting?"

https://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/consensus